When East and West Met in the New Forest. 1914 to 1916

I have written about the Indian army units in Hampshire that were based at Ashurst from October to December 1914 and in the hospitals at Brockenhurst and Bournemouth along with the Indian convalescent depots at Milford and Barton-on-Sea. The Indian medical facilities opened in late October 1914, eventually closing in March 1916. In this article we will review how the local residents and the Indian soldiers interacted with each other when ‘East met West’.

When the Indian Artillery unit arrived at Ashurst in October 1914 to re-equip with more powerful guns and to use the open heathland to train in their use, the local population were immediately interested in them. ‘The Lymington and South Hants Chronicle’ dated 22nd of October 1914 advertised coach trips from the Angel Hotel in Lymington to visit the Indian camp. On the 28th of October a reporter for ‘The Times’ wrote about the visit he made to see the Indian soldiers. He described it as ‘a gypsy like spectacle’ and visitors came to meet the soldiers from as far away as Bournemouth. He vividly described the Indian soldiers going about their business in camp, cooking, tending to the horses and mules, cleaning their equipment whilst ‘a trinity of giggling women snap at them with their cameras and discuss their beauties and their attitudes’. He wrote that gifts of chocolates had been given to some of the soldiers, who had shared them with a local child.

To give some idea of the scale of the casualties suffered by the Indian army in France and Belgium it is worth pointing out that two divisions of infantry (9,500 men) and one brigade of cavalry (1,700 men), forming the Indian Corps arrived in Marseille on 26th September 1914 and by the 22nd of October were in the front line. By the 1st of December 1914 they had suffered 228 officers and 4735 other ranks, killed, wounded, missing or sick.

The casualties arrived by hospital ship at Southampton docks and then by train to Brockenhurst. They were taken to the Balmer Lawn Hotel and the Forest Park Hotel, which had been converted into hospitals. In January 1915 a purpose-built hospital came into use. It was located at Tile Barn on land loaned to the War Office by Mrs Morant of Brockenhurst Park. The new hospital consisted of wooden huts with tin roofs and sidings connected by covered corridors. There were two operating rooms, an X-Ray room and a laboratory. It was capable of dealing with 500 patients. The site, known locally as ‘Tin Town’ was officially named the Lady Hardinge Hospital. Lady Winifred Hardinge had been the wife of Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India. Both had done much to promote public health reform in India. To allow the hospitals in Brockenhurst and Bournemouth to accept fresh casualties there were convalescent depots set up at Barton-on-Sea and at Milford-on-Sea. Wounded and sick patients were sent to the hospitals in the first instance. When their condition improved, they were posted to a convalescent depot, thus freeing up a hospital bed.

The Royal visit to Brockenhurst on the 17th of November 1914 was reported in both national and local papers, bringing the Indian wounded to the attention of the nation. Local residents were equally friendly to the Indian convalescents when they started to venture into the village. Mr John Martin ran a chemist shop in Brookley Road, Brockenhurst and he was also responsible for taking many of the photographs of life in wartime Brockenhurst and of the Indian visitors.

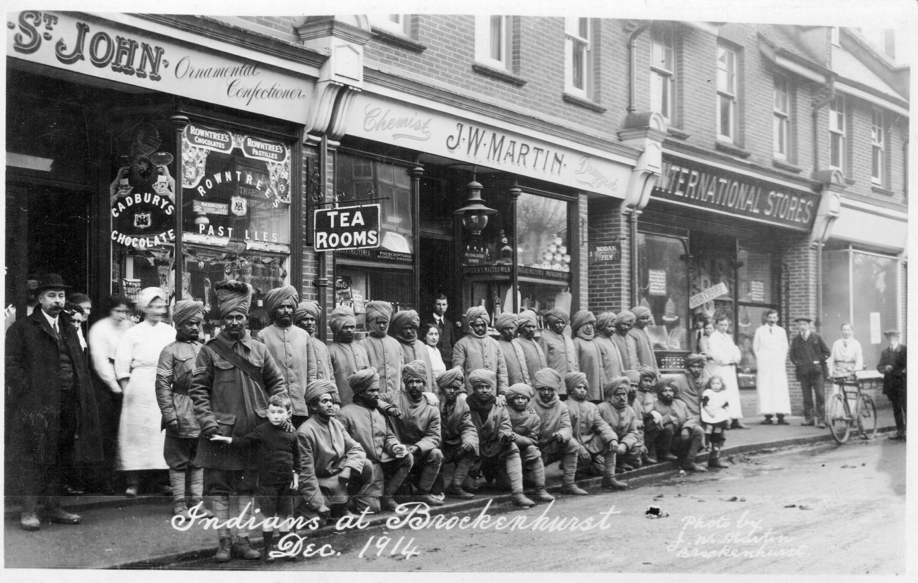

Indian soldiers in Brookley Road. Courtesy of the Tony Johnson collection.

One image, dated December 1914 shows Indian soldiers posing for a photograph outside Mr Martin’s shop. Local residents look on but are slightly apart from the visitors, although one young lady is standing in the middle of the back row. The people in the image appears somewhat stilted, perhaps they needed to stay still for the camera. Later photographs show a more relaxed attitude between locals and Indians. Mr Martin’s son Ken and daughter Phyllis are holding hands with the Indians at either end of the line.

The soldier’s enjoyment of playing with the children broke down barriers between them and the locals. In a December 1917 dated account of life in Milford-on-Sea in World War One, published by the Milford-on-Sea Historical Record Society (MOSHRS) the author wrote ‘perhaps the most marked characteristic of our friends was their fondness for little children for whom they would do anything, often to the embarrassment of wheelers of perambulators’. Note the Indians are described as ‘our friends’.

When Indian convalescents were invited to a vicarage garden party at New Milton, local school children performed Maypole and country dances for them. Afterwards, in a translated speech of thanks the soldiers said that they ‘loved to watch the children, who reminded them of the little ones they had left behind’. The tolerant attitude of many local residents towards the Indian soldiers helped to strengthen the growing friendships. A letter published in the Milton Parish Magazine recorded that one local resident was visited, unannounced by two Indian convalescents. It was raining and using sign language the men asked to take shelter in the porch. The writer allowed this and offered them cigarettes which they refused in preference for coffee. They asked if they could come into the house to wash and freshen up. Again, the local resident allowed this. After their ablutions they shook hands with the householder and left.

Indian soldiers were invited to the homes of local residents and made to feel welcome. MOSHRS have a copy of a letter Sokam Singh of the 35th Sikhs Battalion wrote to a Mr Brace of Milford-on-Sea accepting an invitation to afternoon tea and enclosing a list of useful Indian phrases. One villager recalled ‘their greatest desire was to see the interior of our houses, and frequent requests were “see house”’.

Gift were given by local people to the Indian patients. Reverend John Edward Kelsall of Milton Parish offered guidance to local residents on how to look after ‘Our Indian Visitors’. He provided a list of suggested acceptable gifts in the parish magazine and arranged for a collection point at the local grocery shop in the village. Reverend Kelsall then took the items up to the Barton-on-Sea Convalescent Depot.

Gifts were also given by Indian soldiers to the local residents. In Milford-on-Sea the patients frequently visited the local shops, making purchases and browsing the goods on display. They ‘liked to bring little tokens to the shopkeepers’ and when one local tried to reciprocate the Indian ‘drew himself up to his full height and in a dignified voice said “want nothing”’. Soldiers gave photographs of themselves to local residents on leaving. In Milford-on-Sea it is was known that any bicycle left unattended in the village was considered ‘fair game’ by the Indian soldiers who would pedal around the locality. Coming down Barnes Lane as the road became steeper, crashes occurred. On several occasion when Mrs Hobby went out to tend to the casualties, she was presented with brass water vessels as a gift and on one occasion a Sikh turban.

Indian water vessel given to Mrs Hobby in Milford-on-Sea. Courtesy of the Chris Hobby collection.

The local clergy often led by example in terms of friendship shown towards the Indian soldiers. At the Lady Hardinge Hospital an Indian sweeper named Sukha died of pneumonia on the 12th of January 1915. He was of low caste and the Hindu religious authorities would not cremate him. Similarly, the Muslim clerics declined to bury him. Reverend Arthur Chambers, the vicar of Brockenhurst agreed to inter Sukha even though he was not Christian. The local villagers made donations to pay for a headstone for Sukha’s grave. Some residents were less friendly. In January 1915 Mr T.E. Coverdale published a letter in The New Forest Magazine urging local English women not to shake hands with Indian soldiers or interact with them as it was disrespectful to the English ladies and embarrassing to the Indians. Reverend Chambers responded, condemning Coverdale’s letter as being in ‘very bad form’ and would give ‘our Indian friends a very poor idea of […] our gratitude to those who have done more for us then we are ever likely to do for them’. Through the leadership of the clergy, local residents were set an example of how to behave in a benevolent way to make their Indian guests feel more welcome, although not everyone followed that example.

Some of the photographs from that period suggest that the relationship between the local residents and the Indian soldiers was a strong one.

Milford on Sea residents mixing with Indian soldiers. Courtesy of the Chris Hobby collection.

This photograph is clearly posed owing to the equipment used however, there is evidence of genuine friendship. The image shows Indian soldiers, Milford-on-Sea residents and children interacting with each other. Two soldiers have their arms linked with the ladies next to them. One also has his hands on the shoulders of a small child. The group appears to be relaxed with each other and does not show the stiffness apparent in the December 1914 image.

Indian soldiers were willing to become involved in local events. Khudadad Khan was the first Indian soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross. He recovered from his wounds at the Barton-on-Sea convalescent depot. The January 1915 Milton Parish magazine records that he attended a meeting in the village school to lend his support to the recruiting drive. Reverend Kelsall of New Milton was a keen conservationist. He instigated the planting of trees alongside Barton Court Road and Avenue, leading from New Milton to the Indian convalescent depot on the cliff tops. Not only did local residents plant a variety of specimens, so too did Indian soldiers. Reverend Kelsall, recorded the names of those men in the parish magazine stating that they represented four of the Indian nations. At the planting ceremony, speeches were given in three of the languages of India. One Christian Indian soldier, Frank Maya Das was invited by Reverend Kelsall to plant a lime tree in the Rectory Garden. The Reverend ensured that all the local school children were present in the audience, along with Indians and local residents as he wanted to preserve the memory of the soldiers stay in the village for as long as possible. During the speeches, it was pointed out that one third of the population of the village at that time, was Indian. Local residents were also willing to be involved in the Indian soldiers’ social activities. On the 2nd of August 1915 there was a sports competition held between the convalescent depots of Milford and Barton. About 3000 guests attended including many local villagers. A field was lent to the soldiers by Mr Farwell, a local farmer and many of the cash prizes were donated by locals. As a result of the growing friendship between the Indian soldiers and local residents, they were willing to involve themselves in social and civic events that further strengthened local community cohesion.

Programme sellers for the Indian Sports Day at Barton. Courtesy of the Chris Hobby collection.

The Indian soldiers wrote letters to family and friends. These letters, were censored and copies were sent to the India Office and are available to be read in the British Library. Several of them record that they are well treated by the locals. One Indian wrote that the local people were ‘of a very amiable disposition, they talk pleasantly, treat us kindly and are pleased to see us’. A soldier in Milford-on-Sea wrote that he had chores to do in the morning but later could visit the shops, go to the seaside or sing round the piano in a local house. He asked his family if they would be upset if he married locally.

Whilst the Indian troops did face racial discrimination from some quarters during their stay in England there is much evidence to suggest that a local level the soldiers and New Forest residents got on well together and friendships were formed.

The Indian soldiers are remembered in Barton-on-Sea with a memorial that was unveiled on 10th of July 1917. This week a local Friends of the Indian Soldiers’ Monument (New Forest) was formed to organise the annual 10th of July commemoration ceremony, to celebrate the shared cultural heritage and promote the history to a wider multicultural audience.